BASICally Speaking

Computer programming for the rest of us in the 1960s and beyond

One of my earliest nerd memories takes place around 1969, when I was in 8th grade at East Junior High School in Aurora, Colorado. Our beloved science teacher, Mr. Klotz — a man with the patience of a saint who became a personal mentor to me — led our class to the boys’ gym for what he promised would be “a special surprise.”

A Teletype Model 33 ASR connected to a MITS Altair 8800 computer. Note the rolled-up paper tape on top of the computer. Image by Tim Colgrove via Wikimedia.org under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

What awaited us was not a cake, a rocket, or even a taxidermied frog wearing a lab coat. Nope — it was a Teletype Model 33 ASR (Automatic Send/Receive). This, my friends, was the Cadillac of slow, noisy, UPPERCASE-ONLY data terminals. It came complete with a keyboard that required the strength of a minor deity to press, a paper tape reader (for storing your digital masterpieces in a series of holes in a one-inch wide roll of beige paper), and an acoustic coupler — a device designed to let your Teletype whisper sweet nothings to a computer over a 110-baud dial-up connection.

Let me be clear: the Teletype was not a computer. It was the keyboard and printer for a computer. Specifically, a Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-8 at the school system admin building running a time-sharing system known as TSS-8. This meant a bunch of junior high kids could dial into a far-off computer and share time on it — presumably when it wasn’t busy calculating lunar trajectories, printing class schedules, or winning chess tournaments.

Our first assignment? Play tic-tac-toe against the machine. Over and over. The clattering, the whirring, the SCREAMING CAPS LOCK — it was glorious! And as we slowly got better at outsmarting the PDP-8, I began to realize I was falling in love. Not with tic-tac-toe, but with technology.

The Teletype had a distinct smell — like hot electronics, mechanical grease, and burning paper mixed together in an electromechanical incense. The printer’s motor ran constantly and heated the case to “caution: egg-frying” temperature. It even had the word HOT printed on top, just in case you were thinking, “Hmm, I should probably stick my fingers in there.” (Spoiler: I did. So did my buddies. It was a rite of passage.)

Also hidden inside was a mechanical bell. Not a cute electronic beep, but a real, honest-to-goodness hotel-desk-style DING! If you typed Control-G, the bell rang. So naturally, I wrote programs that rang it repeatedly until a responsible adult screamed “MAKE IT STOP!” and hit Control-C like they were launching nukes.

Though I never became what you’d call a “real” programmer (i.e., no hoodie, no startup, no coffee addiction), I spent a surprising amount of time writing code over the years. It all began with one magical, slow-as-molasses language: BASIC.

And I do mean slow. BASIC was originally designed for use over dial-up at 110 baud. That’s 110 bits per second, or roughly 11 characters per second — assuming each character was perfect and you weren’t typing like you were hammering spikes into railroad ties. To put that in perspective, my current home internet connection runs at 845 million bits per second. The Teletype would spontaneously combust if it even heard about speeds like that.

So yeah, we’ve come a long way since 1969. But I’ll never forget the day Mr. Klotz introduced us to the magical, clunky, bell-ringing monster that sparked a lifelong love of tech. And it all started in a junior high gymnasium filled with kids, curiosity, and the soothing DING of the future.

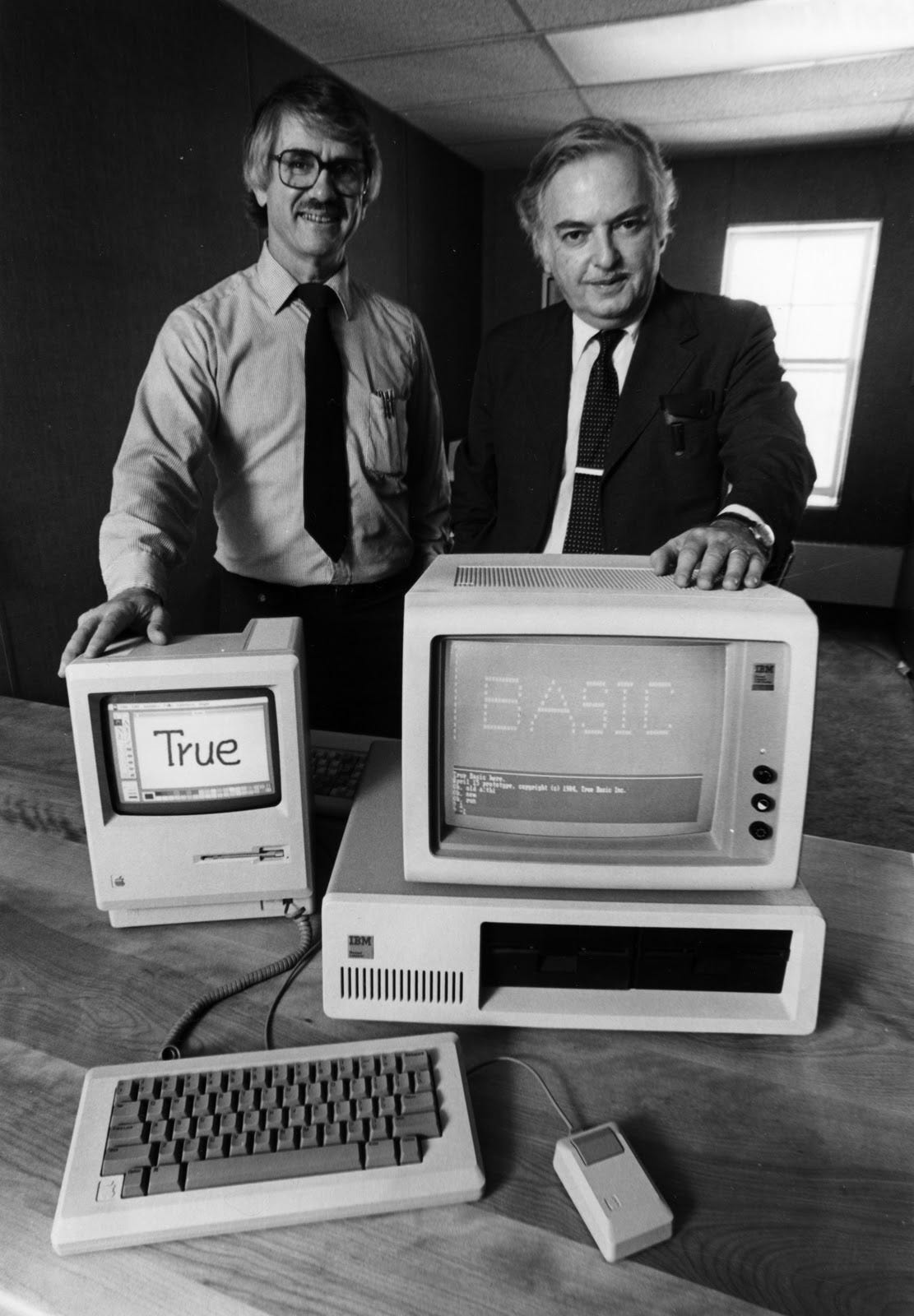

BASIC inventors John Kemeny (right) and Thomas Kurtz. Picture source is unknown.

BASIC Instincts

BASIC — which stands for Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code — was invented by John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz at Dartmouth College (now Dartmouth University) back in 1964. Their goal? To take the mysterious, intimidating world of programming (where only engineers, scientists, and Bond villains dared to tread) and open it up to mere mortals — like art majors and 8th graders.

Unlike the cryptic incantations of assembly language or the stone tablets of FORTRAN, BASIC used English-like commands that even a hormone-riddled teenager could understand. Commands like IF, THEN, GOTO, PRINT, and the emotionally satisfying END. All you needed was a vague sense of logic and fingers of steel to survive the Teletype keyboard.

Amazingly, BASIC is still around, more than 61 years after its May 1, 1964 debut. Not bad for something originally designed to help college students make math class slightly less soul-crushing.

Of course, not everyone was a fan. Dutch computer scientist Edsger W. Dijkstra once growled:

“It is practically impossible to teach good programming to students that have had a prior exposure to BASIC: as potential programmers they are mentally mutilated beyond hope of regeneration.”

Gee, Ed, tell us how you really feel.

But don’t worry — I turned out (mostly) fine. After my BASIC beginnings, I moved on to the engineering heavyweight language of the ’70s: FORTRAN. It was like trading in a Big Wheel for a Volvo — not flashy, but it got the job done.

By the early 1980s, as personal computers became less “hobbyist curiosity” and more “everyone-has-one-except-grandma,” BASIC had become the lingua franca of home computing. Most machines came with some form of BASIC interpreter baked right in — because what else were you going to do with 16K of RAM and no hard drive?

Now, most people couldn’t actually write games or software from scratch in BASIC, so we had a national pastime: typing in hundreds of lines of code from computer magazines. That’s right — you’d get a glossy issue of COMPUTE! or BYTE or The Rainbow, flip to the 14-page single-spaced program listing in tiny print, and spend the next three hours typing it all in, line by line, praying you didn’t miss a comma.

And if you did miss one? Congratulations! You just broke the entire program and earned a new appreciation for professional developers.

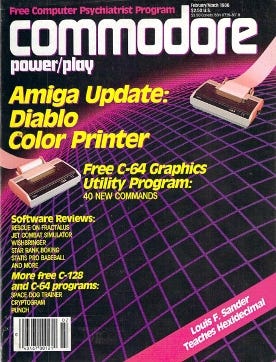

These magazines were extremely tribal. Own a Commodore 64? You subscribed to Commodore Power/Play. Have a Radio Shack TRS-80 Color Computer? You were reading Hot CoCo. (Yes, that was a real magazine title, not a breakfast cereal.) And so it went — every computer had its own cult and corresponding stack of magazines.

Speaking of BASIC — did you know Microsoft’s very first product was a BASIC interpreter? That’s right, Bill Gates and Paul Allen whipped up a version of BASIC for the MITS Altair 8800, one of the earliest personal computers. The story of how that all came together (and why “Micro-soft” had a hyphen back then) is a juicy one — but I’ll save that for a future LifeBits entry.

Back at East Junior High, computing was still a bit of a novelty. We had one Teletype in 1969, and it rotated between schools like a substitute gym teacher. But by the time I was a junior at W.C. Hinkley High School, we’d entered the big leagues — a fleet of Teletypes and an actual Computer Algebra class!

That class was the gateway drug: algebra by day, programming by night. We’d get math assignments and then write code to solve them. It was like Mr. Klotz had joined forces with HAL 9000 — but in a good way. In fact, that class may have done more to prepare me for engineering school than anything else in high school (apologies to Miss Francis, my eighth-grade typing teacher).

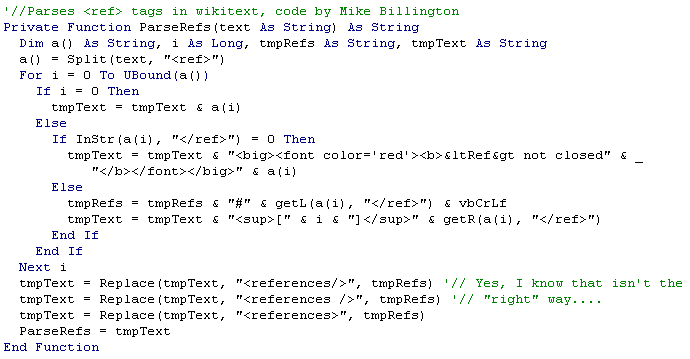

Sample Visual Basic 6.0 code. Screenshot by Michael Billington. Public domain image via Wikimedia.

BASIC Today

BASIC made a bit of a comeback in the 1990s and 2000s when Microsoft released Visual BASIC (now Visual BASIC.NET). There was a flavor of Visual BASIC called Visual BASIC for Apps (VBA) that gave users of the Microsoft Office suite (Excel, Word, PowerPoint, Outlook, and Access) the ability to automate repetitive functions, share data between those important apps, and ease data entry through those wonderful forms and windowed user interfaces we’re used to. In my humble opinion, Visual BASIC took all of the fun out of BASIC…

It grieves me to see that BASIC is no longer in the top spot for programming languages for beginners. The crown of 1970s nerdiness has been passed to Python and JavaScript, and BASIC doesn’t even make the cut in top 10 lists. Many of us old-timers now have to commiserate in places like the Facebook “BASIC Programming Language” group, which we peruse on our smartphones while telling kids to get off our lawns.

That’s not to say that you can’t still play with BASIC. There are a ton of ways to code in BASIC, often in a web browser emulating one of the old “flavors” that existed like Commodore BASIC, Microsoft QuickBASIC, and AppleSoft BASIC. Sadly, nobody has created a Teletype Model 33 emulator to pound the keys on, but that’s progress!

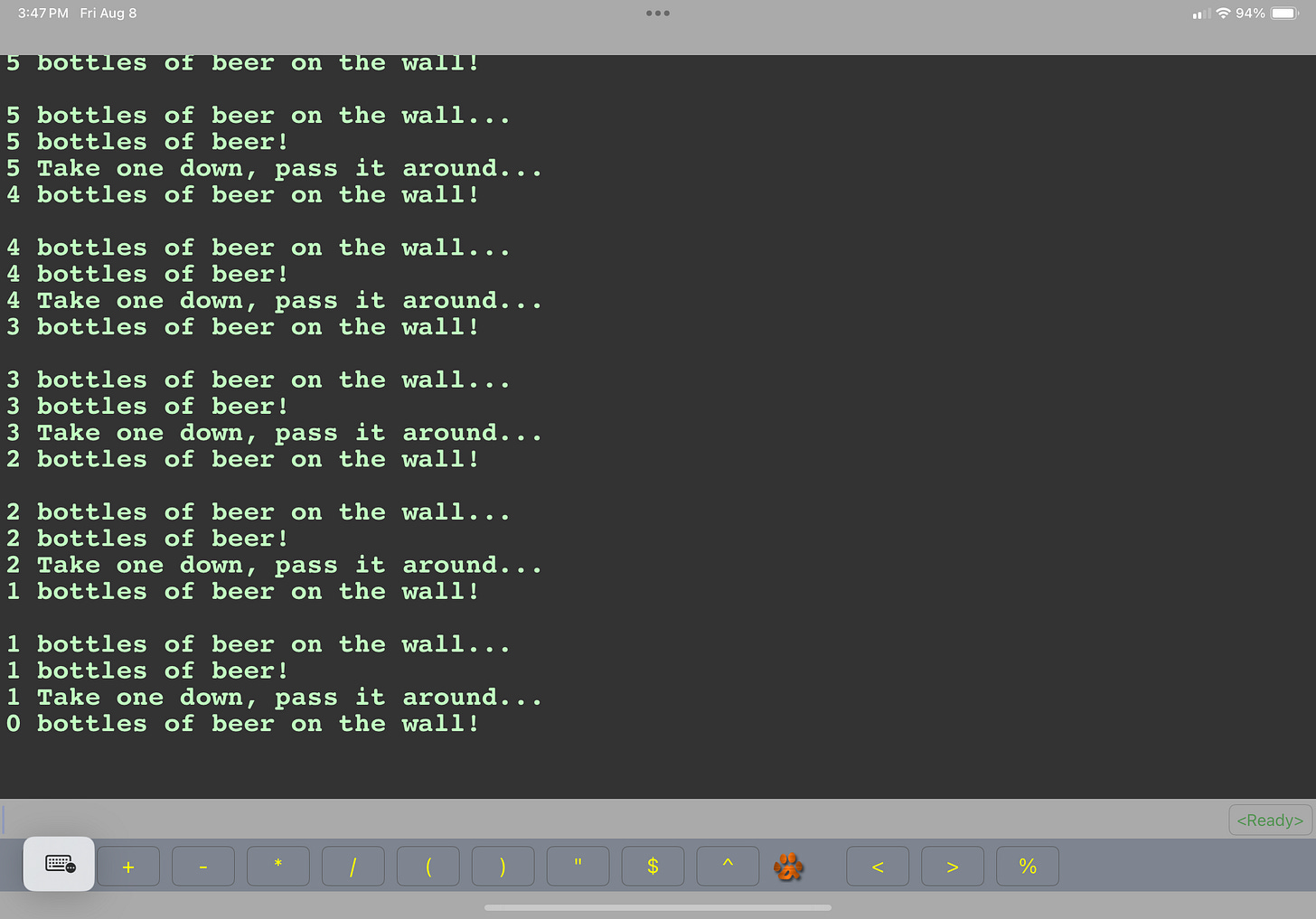

Just to prove that I still have incredible BASIC programming skills at this time, I found a decent version of BASIC that would run on my iPad and iPhone, loaded it, then cranked out this important and very useful program:

It produces the following output, which I need to slow down so me and my buddies can sing along to the lyrics. Currently, I don’t think I could drink one bottle of beer in the amount of time it takes to get from 100 to zero bottles of beer (on the wall).

See? Who says that useful, life-changing programs can’t be written in ancient programming languages for beginners?

The beautiful simplicity of BASIC is apparent in this example. Need to leave a remark in your code? Start a line with “REM”. Want some output on the screen? Use PRINT. How about checking to see if a condition has been met? Use an IF… THEN statement. Those are just the basics (no pun intended), and every version of BASIC has its own flock of statements, commands, functions, and operators to turn it into a toolkit for exploration of computer science!

My upcoming not-so-secret project is to get this same BASIC editor/interpreter (HotPawBasic) in the flavor that runs on a Raspberry Pi single-board computer, then write some programs that will actually have utility that I can run on a sub-$100 computer in our RV. That sounds like a future LifeBits article to me…

Thus endeth the fourth chapter of Steve’s Epistle to the Nerds, AKA LifeBits. Could you do me a favor? If you were even mildly entertained by this post or learned something you didn’t know before, could you please “Like” this by clicking/tapping that “heart emoji” at the top of the page. And if you’d like to take more of these trips down memory lane, subscribe to LifeBits to get this in your email inbox every time a new post oozes out of my brain.

Until next time… don’t burn your fingers with a soldering iron.