Bytes Before Broadband: The BBS Days

BBSs for pleasure, work, and as a hobby

A weird AI “dream” of how my office may have appeared in the days of the MAGIC BBS. Image generated by ChatGPT (OpenAI) using the DALL·E model.

When I got my first personal computer in the summer of 1982 (a Commodore 64), one of the things I decided to do was see if I could connect to a Bulletin Board System (BBS). Now, that computer didn’t do too much, but it was capable of doing things that “real” — and much more expensive — personal computers like the Apple II and IBM PC handled, like word processing, spreadsheets, games, and telecommunications.

The way most of us found out about computer-related things in the 1980s was through magazines. I was partial to Byte Magazine, which always seemed to know what was going on across the nascent personal computing world before any other source did. It was in a Byte issue sometime in 1982 that I saw two things that caught my eye — an article about bulletin board systems that were seemingly popping up everywhere — and an ad for an inexpensive Commodore-branded modem.

The amazing Commodore Model 1650 Automodem: Image from pagetable.com.

Now, what the heck was a modem? That’s a contraction of modulator/demodulator, which Wikipedia defines as “a computer hardware device that converts data from a digital format into a format suitable for an analog transmission medium such as telephone or radio.” They’re still around — my current cable-based internet service uses a cable modem to give me speeds of up to 1 gigabit (1 billion bits) per second.

Back in the early days, you’d plug your phone line into one of the ports and another one went between the modem and a telephone. You could switch most modems to an “auto-answer” mode, which meant that anyone who called your phone number would be greeted not by your sultry voice, but by that wonderful screech we associated with modems. Fortunately, most modems also had a D/T switch that allowed the device to switch between data usage (D) or telephone (T).

The modem of my desire was the Commodore Model 1650 Automodem, which operated at the blinding speed of 300 baud. The reason I wanted this particular modem was that it came with software on a cassette tape that enabled the computer to dial into online services like Dow Jones News/Retrieval and the Commodore Information Network.

The latter was a subsection of CompuServe, an online service that was booming at the time. The main reason for CompuServe’s success? Most big cities had a local phone number you could dial into — remember, these were the days when long-distance phone calls were expensive! So you’d dial into that local number with your telecommunications software and modem, and be connected to the entire CompuServe service.

I didn’t like CompuServe for a number of reasons, but primarily because they charged a monthly fee for their service. If only I could have looked into the future and viewed today’s world where everything is a subscription! So what did I dial into instead? Bulletin Board Systems.

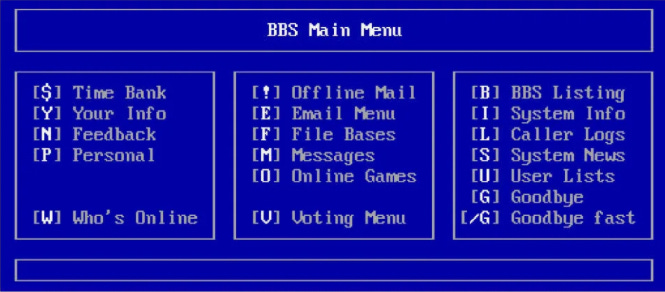

Most BBSs had the same functions in common: a message board, a way to share files, and sometimes even a way to have discussions with other users (for BBS’s that had more than one dial-up line available). Think of a bulletin board system as the caveman equivalent of online forums and social media.

The early BBS menus were quite similar in how they looked and operated. This was all text-based, although later BBS hosting software provided Mac users with the familiar graphical interface.

Sample BBS Main Menu actually taken from a sticker that is for sale online…

Email? It may show be a menu item in that picture above, but it was not on the systems I used in the early days. Instead, there were message boards, lists of other BBS phone numbers, and the ubiquitous file download areas where you could grab public domain software or (on some notorious sites) copies of pirated “real software” that someone had removed copyright protection from… As I was running a BBS, I kept away from hosting the pirated stuff on my system as I had a fear of lawyers.

In the days of the Commodore 64, my online sessions were usually something like this.

Turn on the computer and monitor

Let the computer boot up

Turn on the cassette drive (later a disk drive) used to load software, and make sure it is attached to the computer

Type in the commands to load the software from the cassette or disk

Tell my wife that I was going to tie up the phone line and not to make any calls

Connect the phone line to the modem

Run the terminal software and log onto the system

Initially, I typed in the BASIC program that was in the back of the user manual for the Commodore 1650 Modem and saved it to a cassette for future use. I found an old faded printout of this program in a drawer, so this may not be the actual code… I hope none of you were planning on typing this into your Commodore 64 today!

100 OPEN 5,2,3,CHR$(6)

110 DIM F%(255), T%(255)

200 FOR J=32 TO 64: T%(J)=:NEXT

210 T%(13)=13: T%(20)=8: RV=18: CT=0

220 FOR J=65 TO 90: T%(J)=K:NEXT

230 FOR J=91 TO 95: T%(J)=J:NEXT

240 FOR J=193 TO 218:K=J-128: T%(J)-K:NEXT

250 T%(146)=16: T%(133)=16

260 FOR J=0 TO 255

270 K=T%(J )

280 IF K <> 0 THEN F%(K)-J:F%(K+128)=J

290 NEXT

300 PRINT " " CHR$(147)

310 GET#5,A$

320 IF A$="" OR ST <> 0 THEN 360

330 PRINT " “ CHR$ (157);

340 IF F%(ASC(A$))=34 THEN POKE 212,0

350 GOTO 310

360 PRINT CHR$(RV) " “ :CHR$(157):CHR$(146);:GETA$

370 IF A$ <> "" THEN PRINT#5,CHR$(T%(ASC(A&)));

380 CT=CT+1

390 IF CT=8 THEN CT=0:RV=164-RV

400 IF (PEEK(37151) AND 64)=1 THEN 400

410 GOTO 310

As usual, this didn’t work properly for me the first time I tried to run it. Fortunately, my boss at the time was knowledgeable about these things as he had a Radio Shack TRS-80 Model II that he was obsessed with, so he helped me get it working. Once I did, I found the phone number for a local Commodore 64 BBS and logged in… and the first thing I did was to download a decent terminal program.

After that, downloading public domain games, programs and utilities for the Commodore 64 occupied my time, as well as finding the phone numbers for other local C64 BBSs and reading the messages that were left on the board. That was the fun use of bulletin board systems. How about the work use of BBSs I refer to in the subtitle for this article? Well, I’ll write about that in a future LifeBits.

My third use case for BBSs was as a hobby. By the time early 1985 rolled around I was the proud owner of a Mac 512K computer, and I knew that I would have to be a frequent user of the local Mac boards. However, I didn’t like most of them for one reason or another. My brilliant solution in September of 1986 was to start my own Mac BBS called MAGIC (Mac And GS Information Center).

MAGIC, Red Ryder, and The CompuServe Kerfuffle

As a Mac user, I had heard about a wonderful “shareware” terminal program called Red Ryder written by a guy named Scott Watson. Shareware meant that you could download it for free and distribute it to anybody, and if you really found it useful, you’d send a token donation to the developer.

Not only did Watson write Red Ryder, but he also came up with Red Ryder Host, which was BBS software that ran on the Mac. I was in business! I set it my old Mac 512K with its own phone line, and let some of the other local BBSs (and Mac user groups) know about my board.

Somehow, I was able to gain both infamy and fame within a few weeks of starting up the board. Remember my earlier comments about CompuServe? Well, I had an account on there but really didn’t use the service primarily because of the cost. About the only thing I did was to haunt the message boards, and that’s where I posted a short blurb about my new BBS. Imagine my surprise when I got a letter from the CompuServe legal department about two weeks after starting up the site.

The letter was a “cease and desist order” threatening legal action for copyright violations, allegedly because I was “posting software that had been downloaded from CompuServe”. I never downloaded anything from CompuServe because of the cost and the interminable amount of time it took, even with a 1200 baud modem. I wasn’t too happy about this.

Anyone remember InfoWorld? It was a weekly newsmagazine about the IT business (it’s still in existence as a website), and by 1986 I had managed to get my employer to pay for a subscription. Well, I sent them a letter (snail mail…) and told them what was going on with CompuServe. The next thing I knew, an InfoWorld reporter called me and asked some questions about the situation, and had me fax him a listing of the few program files (all in the public domain) that I actually hosted at that time on MAGIC as well as a copy of the letter from CompuServe.

The next issue of InfoWorld contained an article about the situation, which was very sympathetic to me and painted CompuServe as a bunch of suits who were picking on the little guy. CompuServe dismissed its threat, and I ended up getting some very nice national publicity for MAGIC — and a lot more users since the article listed the phone number for the BBS. Note — if anyone can find a copy of that InfoWorld article, please let me know.

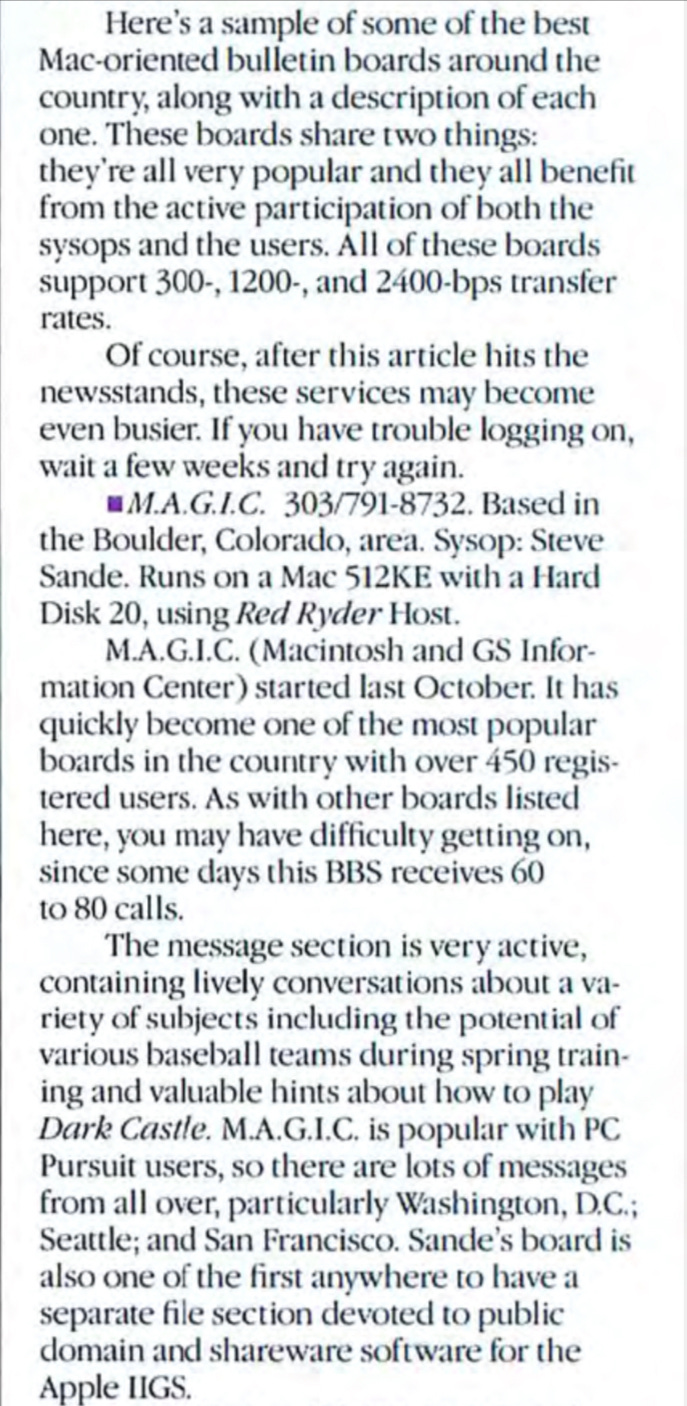

The next level of fame? Fast-forward to this article in the September, 1987 issue of Macworld magazine:

Woo-hooo! Even though they got the location wrong (Highlands Ranch is nowhere near Boulder), the number of users increased significantly, and I decided to add a second Mac (part-time), modem, and phone line to MAGIC (at one point I would have four dial-in lines running on two Macs). All of that had a cost, of course, so I decided to see if I could start charging for a higher level of access.

MAGIC Goes Commercial

As I mentioned earlier, the original MAGIC BBS ran on a piece of software called Red Ryder Host. This was very “un-Maclike” in that people who dialed into the BBS interacted with it just as if they were dialing into any other BBS — there was no graphical user interface. I didn’t like that and wanted to offer the most “Mac-like” (and Apple IIGS-like) interface I could, so I started evolving through different software.

I don’t recall the dates and exact software versions, but the chronology went something like this:

Red Ryder Host

Second Sight (same as RRHost, but with a new name), which became White Knight

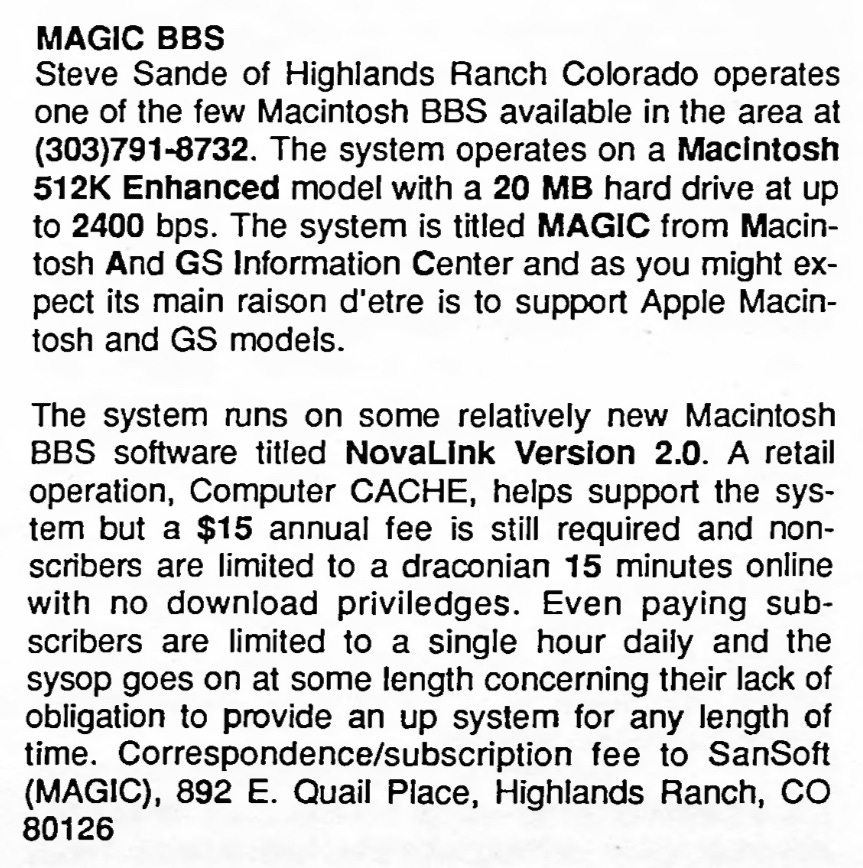

Something called NovaLink 2.0 that I honestly don’t remember

TeleFinder from Spider Island Software, which added a graphical user interface and more capabilities

FirstClass — the last BBS software I ran before starting up my first website. It really looked like the Mac desktop

A screenshot of FirstClass. Image from http://macos.retro-os.live/

Not everyone was thrilled about my idea to charge the onerous amount of $15 per year for full access to the system. I didn’t want people to stay online for hours on end, so each session was limited to 15 minutes for non-subscribers, and subscribers could chalk up an hour a day of online time.

There was a guy by the name of Jack Rickard who published a newsletter called “Denver PC Boardwatch”, and he was quite outspoken in October of 1988 about my decision to actually charge money for better access to a bulletin board system:

Contrary to Mr. Rikard’s opinion, I did not “go on at some length concerning their lack of obligation to provide an up system for any length of time.” I simply had a short disclaimer that people agreed to when signing up that due to equipment failure, busy signals, and software bugs I couldn’t guarantee 24/7/365 service. Sheesh, let’s overreact a bit, Jack!

There was one interesting feature of both TeleFinder and FirstClass — you needed to have the graphical user interface software before you could call into the BBS, and the best way to do that was to give away disks with a customized version that had the phone number(s) pre-loaded. Your users would pop the disk into their disk drive, copy it over to their hard drive (if they had one), then double-click on the MAGIC icon to dial into the site.

I gave away a ton of those disks at user group meetings, and finally one Mac user group (MacinTech — still around, first organized in 1987!) made MAGIC their official BBS. I’m still doing stuff for MacinTech on occasion - I’ll be doing a Zoom presentation for the group on October 14, 2025!

PC Pursuit and Fidonet

You may have noticed a reference to “PC Pursuit” in the Macworld article screenshot earlier. PC Pursuit was a service operated by Sprint (remember them? This was before their days as a mobile telecommunications company) that let people dial into BBSs around the country without incurring long-distance phone call fees. You’d dial an access number, then enter the number of the BBS you wanted to reach, and soon you’d be perusing a website on the other side of the country.

Sprint charged for this service: $30 for 30 hours of off-peak (6 PM - 7 AM) access was much cheaper than a long-distance direct call. If you wanted to call during peak times, Sprint charged $14 an hour. Off-peak hours in excess of the 30 “included” were charged at $7.50 an hour. My use of PC Pursuit was limited to that 30 hours, and I had to really keep track of how many total minutes I had used as I got close to the end of a monthly billing cycle.

But one really cool thing that started expanding in the late 80’s and early 90s was FidoNet. Think of it as an early Internet in which individual BBSs could be linked together, passing along email and files — a network of BBSs linked by phone lines. If you knew a specific user’s FidoNet address, which was in a format like Steve MAGIC@1:250/250.10, the email (which was sent with a subprogram called EchoMail) was passed along from one node BBS to another until it reached the proper place. FidoNet made it possible to send email and files not only locally, but internationally. I remember that my site usually went down for an hour or so each night for what was called the Net Mail Hour when it passed mail and files along to other nodes.

I was familiar with FidoNet from the original (non-networked) PC BBS software that had come out in (I think) 1984 from a couple of alpha nerds by the names of Tom Jennings and Ben Baker. I used the FidoNet software at work as early as 1984 to run a work BBS for project management… but that’s a story for another time.

Of course, being a Mac-based BBS meant that I had to use a non-PC version of the FidoNet “Mailer” called Tabby. Somehow it all worked.

The end of MAGIC / The beginning of PDAntic.com

MAGIC stayed online until (I think) the end of 1993. Why did I give up? I was totally in love with the new girl in town, the World Wide Web. Most of the Internet was dial-up at this point; high-speed connectivity was a thing of the future for home users. I struggled my way through understanding all of the esoteric oddities of this new world, and somehow, some way, put my first website together.

I’ll relate the story of how I got on the Internet for the first time in 1993, then became an early online author of articles about mobile devices (what we called Personal Digital Assistants - PDAs) in early 1994 on a website I cleverly named PDAntic.com.

Could you do me a favor? If you were even mildly entertained by this post or learned something you didn’t know before, could you please “Like” this by clicking/tapping that “heart emoji” at the top of the page. And if you’d like to see more of my trips down memory lane, subscribe to LifeBits for free to get this in your email inbox every time a new post oozes out of my brain. Real fans can subscribe for $5 a month and support my work.

and please share LifeBits with friends!

Until next time… don’t let the CompuServe legal department get you down!