Clive’s Curious Calculator Kits

Two calculator kits from Sinclair that were inexpensive… and weird

Image © 2000, Nigel Tout, VintageCalculators.com

When it comes to British computing legends, probably no one person (well, other than Alan Turing) comes to mind other than Sir Clive Sinclair. He was a likable red-haired inventor, electronics tinkerer, and entrepreneur who was quite ahead of his time. For example, he had a fascination with electric vehicles. In the early 1980s, Sinclair started a company called Sinclair Vehicles and came out with a rather impractical one-seater “tricycle car” called the Sinclair C5. He died in 2021, so I’m hoping that Sir Clive smiled happily at the mass marketing of practical electric vehicles from a variety of manufacturers before he passed on…

His companies (Sinclair Radionics, Sinclair Research, Ltd.) also made some extremely popular and inexpensive personal computers. The first was 1980’s ZX80 (which sold in both pre-built (£99.95) and kit (£79.95) forms) which had a whopping 1K of RAM. It was sold primarily in the UK, although Sinclair did sell both the computers and kits in the US. The ZX81 came out in 1981 and was even less expensive — fully built for £69.95 and as a kit for £49.95. It was a bit more useful since you could buy a 16K RAM expansion cartridge for those larger BASIC programs. Just in case you’re wondering, at the exchange rate at the time that meant that a ZX81 could be purchased in the US as a kit for about a hundred bucks.

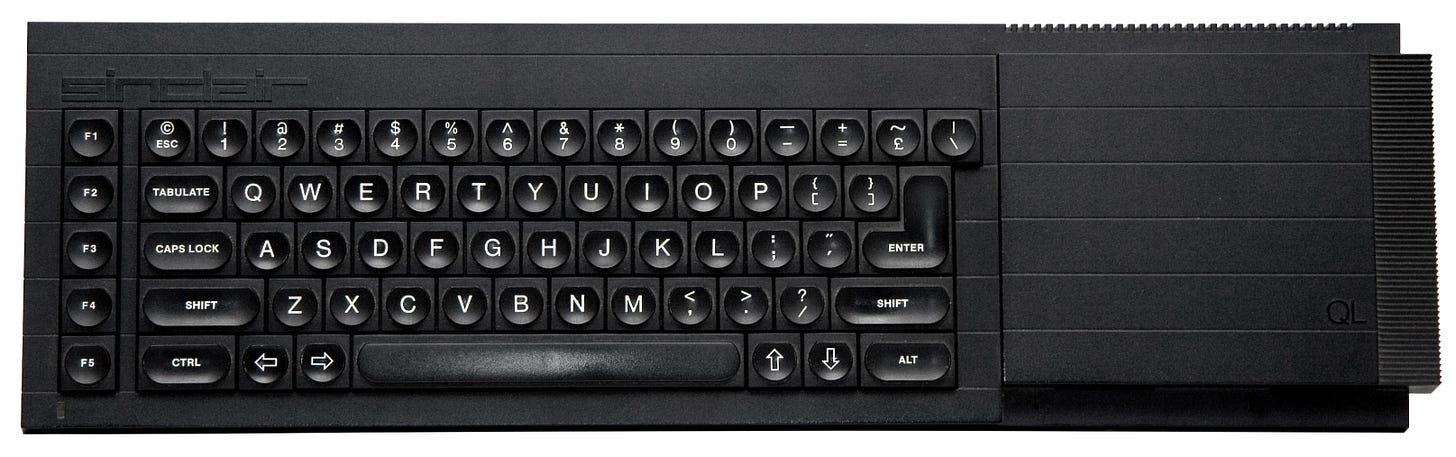

Another Sinclair computer was the ZX Spectrum, which featured a color display (if you connected it to a color TV) and sold for about US$200. This computer, which was sold as the Timex Sinclair ZX Spectrum, sold almost 2 million units around the world. About the same time as the Apple Macintosh hit the market in January of 1984, the last Sinclair computer hit the market. The Sinclair QL used a Motorola 68008 CPU similar to the 68000 used in the Mac, but had some serious issues... despite the fact that it looked quite nice. It was slow, used tape microdrives for storage (rather than diskettes or a hard disk drive), and was never successful.

By EWX, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13983436

Those of us who like to play with the Linux operating system owe a debt of gratitude to the Sinclair QL, since according to Wikipedia:

Linus Torvalds has attributed his eventually developing the Linux kernel, likewise having pre-emptive multitasking, in part to having owned a Sinclair QL in the 1980s. Because of the lack of support, particularly in his native Finland, Torvalds became used to writing his own software rather than relying on programs written by others.[29] In part, his frustration with Minix on the Sinclair[30] led years later to his purchase of a more standard IBM PC compatible on which he would develop Linux.

I never did succumb to one of the Sinclair computers, mainly because in the early 1980s I was still dubious about the future of “home computers”. But I did end up building a couple of Sinclair calculator kits in the 1970s, and those are what this post is all about.

My last LifeBits article was about some of my experiments in electronics kit building, in particular making a pair of electronic synthesizer kits. After having some success in soldering together those two kits, I felt I could build some more useful tools — namely, calculators.

The first was a kit to build my own Sinclair Scientific calculator. At this point I was using an off-brand scientific calculator (see this LifeBits post for more details) to help me get through engineering school, and was salivating at the RPN-based HP calculators that a lot of my fellow students were using .

Money was really a problem for me in college - just ask my wife of 46 years what a cheap SOB I was at the time. I knew I couldn’t afford to buy an HP calculator to get that RPN fix, which is why I took notice of an ad for a kit version of the Sinclair Scientific that came out in the latter part of 1975. What attracted my eye? If I remember correctly, the price of the kit was $30 (plus shipping).

When the kit arrived, it looked like this:

Image via VintageCalculators.com, photo © 2011 Nigel Tout, who runs that website!

There weren’t a lot of components in this kit. That’s where the genius of Sinclair and one of his employees, Nigel Searle, came in. They knew that with fewer electronic components, the cost of the calculator would be less than competing models. As you can see from the image above, there was an LED display (far left), a one-piece bubble-type keyboard (and plastic case front), a printed circuit board, a couple of chips, and a switch. The one chip did most of the heavy lifting was a Texas Instruments TC0805, a microcontroller that was programmed to do scientific functions as a “calculator on a chip”.

Compared to the synthesizer kits, this thing was a piece of cake! It just required soldering three or four pieces to the circuit board, pressing the circuit board into the front of the case, and then pressing the back of the case onto the front. I believe I got it all assembled in about an hour. I popped in four AAA batteries and started to try to figure out how this thing worked. Fortunately, the kit came with a manual.

The first thing that hit me about this calculator was how tiny it was! It measured a scant 50 x 111 x 19 mm (2.0 x 4.4 x 0.75 inches) — truly pocketable. The second revelation was that it was rather inaccurate, at least as compared to my other calculator. That inaccuracy had to do with how they went about having the chip perform scientific calculations. The third annoyance was how it handled numbers — everything was done in scientific notation as it always put a decimal point after the first digit you entered. That was fine if you were trying to add single-digit numbers, but when you wanted to perform calculations on bigger numbers, you had to do a mental calculation of what exponent to use before entering the number.

Let’s say you wanted to enter the number 34,567.4 Rather than just typing 34567, decimal point, 4, you would enter 345674 E 4 — displayed on the LED as 3.45674. In other words, move the decimal point four digits to the right of the first number. Makes a lot of sense, doesn’t it? Likewise, if you did some calculation and got an answer that looked like 6.7346 E 2, your mind would have to look at that number and realize that the answer was actually 673.46. Fortunately the Sinclair Scientific came with a small user manual the same height and width of the calculator that told you how to do all of these things.

Now, about the inaccuracy… The Sinclair Scientific was about as accurate as the usual engineering “calculator” of the day — a slide rule. Compared to the contemporary scientific calculators at the time, the HP-35 and TI SR-50, that wasn’t very good. I won’t go into an explanation of why it was so inaccurate, as someone (Ken Shirriff) has already done so. He’s also created a web-based simulation of the Sinclair Scientific that you can try out.

The Sinclair Scientific kit also had one other annoying problem; the two-part case tended to fall apart, meaning that the back would fall off and the batteries would scatter onto the floor. My high-tech solution to this when it first happened was to wrap a rubber band around the case to hold it firmly together. That looked pretty bad, so I resorted to gluing the two case halves together with model airplane glue for a more permanent and aesthetic fix.

Despite the inaccuracy and other quirks, I really admired the tiny form factor and cool design of the Sinclair Scientific, so I used it when I wanted to impress someone and say “I built this!”

What was the other Sinclair kit? Another calculator. It was selling via mail-order for about $25 (including shipping) and I thought it would be fun… It was the Sinclair Wrist Calculator.

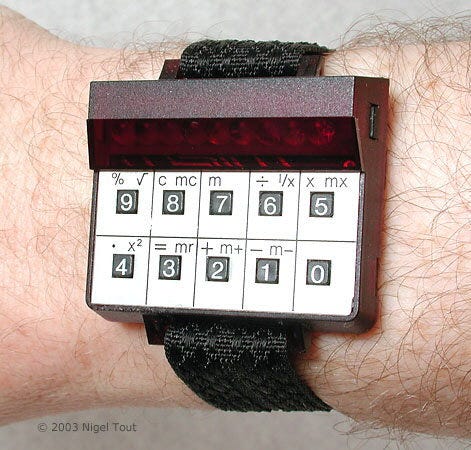

Photo © 2003, Nigel Tout, VintageCalculators.com

Yes, this ugly hunk of plastic was a calculator that strapped to your wrist. It could do the regular four math functions (add, subtract, multiply, divide), plus do percentages, squares and square roots, inverts, and hold partial answers in memory.

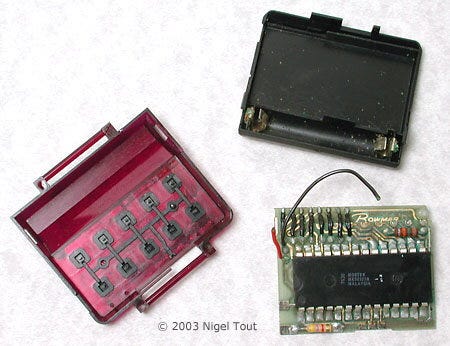

Once again Sinclair had come up with a kit, probably figuring that adding labor to the cost of this device would put it into the “not worth it!” range:

I remember having issues soldering this kit, mainly because the printed circuit board was so small. When assembled, the entire calculator watch measured 47 x 45 x 18 mm (1.9 x 1.75 x 0.7 in). Once the soldering was complete I had to find some mercury button cells (hearing aid batteries) — this thing used six of them for power, stacked end to end.

As with the Sinclair Scientific, the case really didn’t fit together too snugly and had a tendency to pop open. However, since I needed to unsnap the black plastic back from the red transparent plastic front in order to change the batteries, I couldn’t just glue the two halves together. Fortunately, the cheap watch strap that came with the Wrist Calculator was connected to the top (red) part, so if you strapped it onto your wrist tightly enough it kept the back connected.

Even though I was a nerd in the 1970s, I had enough fashion sense to never wear this thing in public unless I was wearing long sleeves. It was truly ugly, and it didn’t work that well either. The issues with keeping the back on also meant that the buttons sometimes pushed the circuit board away without making electrical contact, so it was necessary to push buttons a few times to get them to register. Needless to say, this was an experiment that quickly ended up in the desk drawer, hidden away.

I honestly wish I had kept the Sinclair Scientific. The design of that calculator was quite nice, and it was definitely different. However, not that long after I built the kits I graduated from engineering school, got a pretty decent job, and began to have enough money to buy fun electronic toys.

If you’d like to read more about retro computing and my life in tech, consider subscribing to LifeBits for free. And if you found this glance at tech history to be informative, consider being a paid subscriber! You don’t get anything special for paying for a subscription, except the money generated gives me a chance to try some new techie toys to play with and write about.

It’s also helpful if you “Like” this and other LifeBits posts, as that makes my writing more visible on Substack.

Until next time… go search for some Sinclair products on eBay!